The name of the Devonian period (419–359 million years ago) was established in 1839 by Roderick Murchison and Adam Sedgwick. It derives from Devon, a county in southwestern England (historically known as Devonshire), where the best-documented outcrops of Devonian rocks were found in the 19th century.

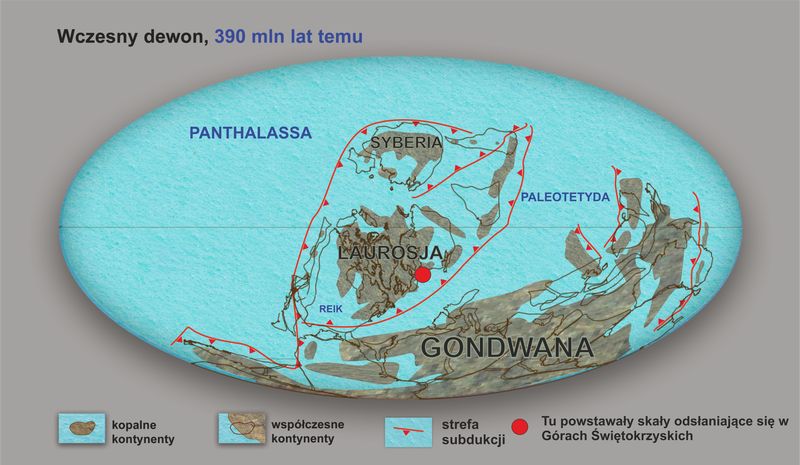

Arrangement of continents in the Devonian with the presumed location of the area where the rocks now exposed in the Holy Cross Mountains were formed. (after Scotese 2016 and Świło et al. 2016, modified)

PALAEOGEOGRAPHY AND CLIMATE

In the Early Devonian, a new continent called Laurussia was finally formed as a result of the collision between Laurentia and Baltica. At the junction of these ancient landmasses, a suture zone developed, accompanied by the formation of mountain ranges known as the Caledonides. Tectonic movements associated with the subsequent Variscan (Hercynian) orogeny also began.

The global climate of the Devonian was characterized by higher average temperatures than today. For most of this period, the polar regions were probably free of ice. Only toward the end of the Devonian did a cooling occur, linked to the glaciation of Gondwana.

Reconstruction of a seashore from the time when the first tetrapods ventured onto land. (after Świło et al., 2016)

LIFE IN THE DEVONIAN

During the Devonian, favourable environmental conditions led to the development of ecosystems resembling modern coral reefs. Their main builders were corals and stromatoporoids—an extinct group of sponge-like organisms. The seas and oceans were inhabited by bryozoans, echinoderms (e.g. crinoids), brachiopods, molluscs (e.g. bivalves and cephalopods), and arthropods (e.g. trilobites). The first ammonoids, a subclass of cephalopods, appeared in the Early Devonian. A key index fossil of this period are conodonts—microscopic, tooth-shaped elements of the feeding apparatus of extinct chordates also known as conodonts.

The Devonian is often called the “Age of Fishes,” as it saw the emergence and diversification of many groups of vertebrates, including sharks resembling modern forms. Ray-finned, lobe-finned, and lungfish evolved, the latter being able to breathe atmospheric air. The seas were dominated by armored jawless fishes (ostracoderms) and armored placoderms, among which was Dunkleosteus—the largest known predator of that time, reaching lengths of over 10 meters.

In the Middle Devonian (Eifelian), vertebrates began to venture onto land. The world’s oldest known footprints of a four-legged animal (tetrapod) were discovered in the Zachełmie quarry (Zagnańsk municipality, Poland). On land, vascular plants such as clubmosses, horsetails, and seed ferns evolved, some resembling shrubs or trees. Insects also appeared. By the Late Devonian, true ecosystems known as the first forests had developed.

Reconstruction of the Devonian seafloor from 380 million years ago: 1 – sponge from the stromatoporoid group, 2 – branching coral from the tabulate group, 3 – solitary rugose coral, 4 – sponges of the genus Amphipora, 5 – placoderm fish of the genus Coccosteus, 6 – placoderm fish of the family Ptyctodontidae (after Pytlik 2012, modified)

THE DEVONIAN EXTINCTIO

The Devonian period ended with one of the most significant mass extinction events in Earth’s history. This crisis, which occurred in several stages between 375 and 359 million years ago, primarily affected marine ecosystems. It led to the disappearance of many reef-building organisms, including stromatoporoids and tabulate corals, as well as numerous groups of brachiopods, trilobites, and ammonoids.

The causes of the Devonian extinction are still debated. Scientists suggest that a combination of factors was responsible, including global cooling following the glaciation of Gondwana, sea-level fluctuations, ocean anoxia (oxygen depletion), volcanic activity, and possibly meteorite impacts.

These environmental changes dramatically altered the biosphere and paved the way for the dominance of new groups of organisms in the Carboniferous period, such as amphibians and the first extensive forest ecosystems.

DEVONIAN ROCKS IN POLAND

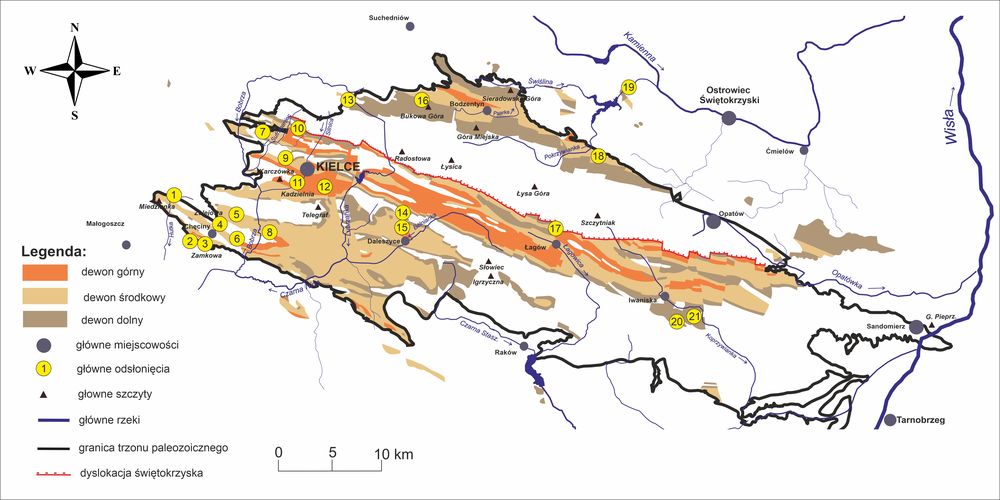

The most numerous outcrops of Devonian rocks, showing great lithological diversity, are found in the Holy Cross Mountains, where the entire Devonian succession can be observed. Rocks from this period are also exposed in the Kraków–Częstochowa Upland (e.g. in the vicinity of Siewierz, Klucze, and Dębnik near Kraków) and in the Sudetes (e.g. the Bardzkie Mountains, the Kaczawskie Mountains, the Strzelin Hills, and the area around Świebodzice).

The most important Devonian outcrops in the Holy Cross Mountains with the indicated extent of Devonian rock occurrences (the extent does not include Quaternary cover): 1 – Ostrówka, 2 – Rzepka Hill, 3 – Zamkowa Hill, 4 – Zelejowa Hill, 5 – Szewce, 6 – Bolechowice, 7 – Mogiłki, 8 – Kowala, 9 – Ślichowice, 10 – Trójeczna Hill, 11 – Kadzielnia, 12 – Wietrznia, 13 – Zachełmie, 14 – Józefka Hill, 15 – Podłaziana Hill (Świnia Góra), 16 – Bukowa Góra, 17 – Łagów-Płucki, 18 – Skały, 19 – Doły Opacie, 20 – Ujazd, 21 – Kopiec. (after Szczepanik 2015, modified)

THE DEVONIAN IN THE HOLY CROSS MOUNTAINS

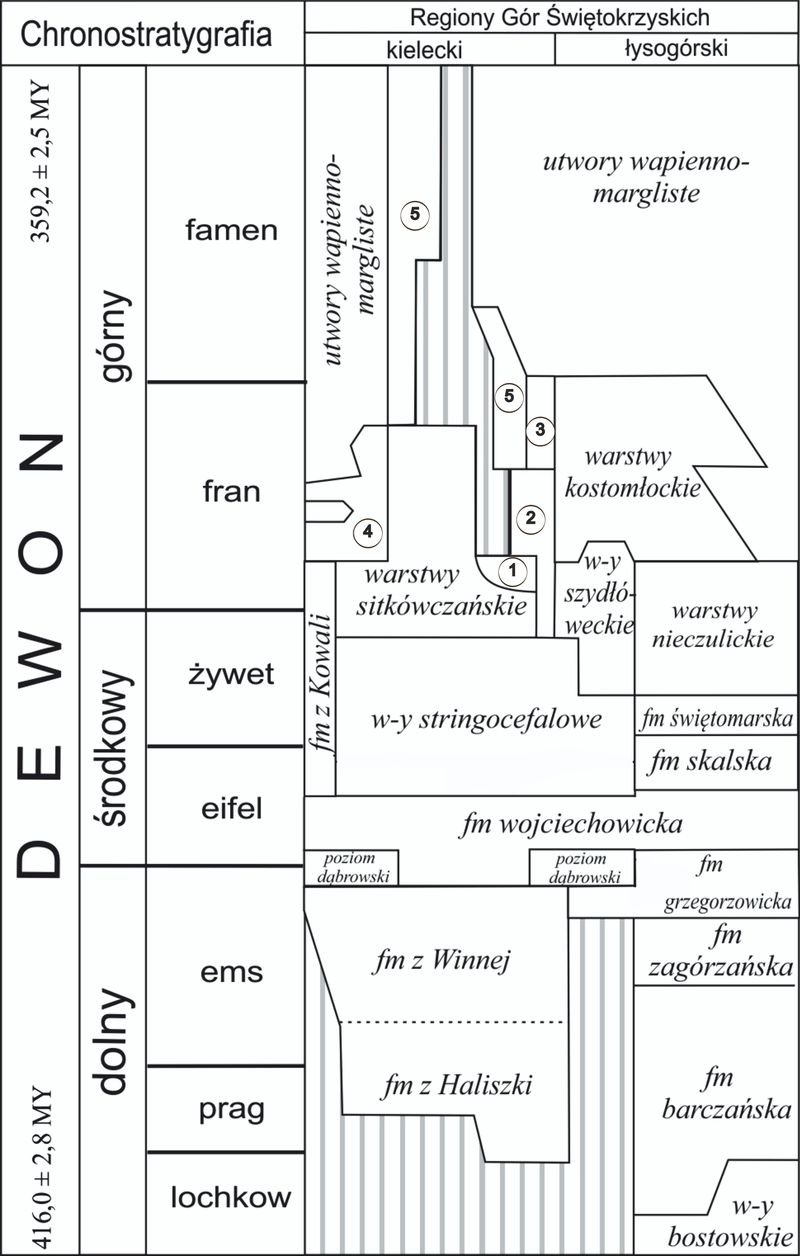

- The Holy Cross Mountains host some of the world’s finest and most complete exposures of Devonian rocks.

- During the Devonian, the area in which the present-day Holy Cross Mountains formed was located in the tropical belt along the eastern coast of Laurussia.

- The Lower Devonian is represented by terrestrial, deltaic, and shallow-marine deposits. Numerous fossils can be found there, including brachiopods in the so-called spirifer sandstones (e.g. Bukowa Góra) and fish or jawless vertebrates in placoderm sandstones (e.g. near Daleszyce).

- In Lower Devonian sandstones on Trójeczna Hill, scientists discovered the world’s oldest fossilized advanced root structures—evidence of plants that may have reached heights of up to 5 meters.

- In the Zachełmie quarry, footprints of the world’s earliest known four-legged animals (tetrapods) were found in Middle Devonian dolomites dated to about 393 million years. Owing to this discovery, the Zachełmie site has been included among the 100 most important geological heritage sites of UNESCO.

- In the quarries at Ujazd, Zachełmie, and Kopiec, exceptionally well-preserved feeding traces of fish—impressions of their mouths in sediment—have also been found and described.

- At the Skały quarry, within Middle Devonian carbonate rocks, the world’s oldest known fossil coral reefs of intermediate depth (located between 30 and 150 meters below sea level) have been identified.

- The Kadzielnia, Chęciny, and Zelejowa limestone ranges near Kielce and Chęciny are composed of Middle Devonian limestones that formed in warm, tropical shallow seas. On their sea floors, reef ecosystems developed—analogous to modern coral reefs—built mainly by corals and stromatoporoids.

- In the Kowala quarry, a unique world-class discovery was made: fossilized rows of migrating trilobites. Although these animals lacked visual organs, they likely communicated chemically through substances released into the water, moving one after another. This is considered the world’s oldest evidence of such collective movement and communication.

- The Late Devonian extinction is also clearly recorded in the rock sequences of the Holy Cross Mountains, providing valuable insight into one of Earth’s major biotic crises.

Simplified lithostratigraphic scheme of the Devonian in the Holy Cross Mountains: 1 – Kadzielnia Massive Limestone Member, 2 – Laskowa Hill Limestone Member, 3 – Manticoeras Limestones, 4 – Detrital Limestones, 5 – Condensed Crinoidal–Cephalopod Limestones. (after Szulczewski 1995; Stratigraphic Table of Poland 2008; Narkiewicz & Narkiewicz 2010; Fijałkowska-Mader & Malec 2011; Skompski 2012, modified)

The Devonian rocks of the Holy Cross Mountains have been used in construction for many centuries. Particularly noteworthy are the so-called Chęciny (Kielce) marbles—colourful limestones, mainly of Middle Devonian age, whose decorative qualities result from fossil content and calcite mineralization. As early as the 16th century, they were quarried in a relatively small area between Kielce and Chęciny and processed in the stone-carving workshops of the Chęciny centre. They were primarily used to produce facing, flooring, and epitaph slabs, and less frequently for architectural elements such as columns, balustrades, or tombstones. The last active marble quarry, Bolechowice, still operates periodically.

Today, Devonian rocks are quarried and processed for various purposes—including construction (e.g. aggregate production) and several industries: lime, cement, chemical, and metallurgical (as flux or for glass production), as well as agriculture (for fertilizer production). Mining activity is concentrated in the area between Kielce, Chęciny, and Miedzianka, as well as near Łagów.

It is worth noting that the centuries-long history of Devonian rock exploitation around Kielce and Chęciny has greatly contributed to a better understanding of the region’s geology, as each anthropogenic exposure has provided (and continues to provide) valuable scientific insights.

For example, the historic quarries within Kielce—Kadzielnia, Wietrznia, and Ślichowice—are now protected as nature reserves of inanimate nature. The exceptional geological heritage of this area formed the basis for the establishment of the Chęciny–Kielce Landscape Park in 1996, which, since 2021, has also been recognized as part of the Holy Cross Mountains UNESCO Global Geopark.

O geologii regionu świętokrzyskiego i nie tylko

O geologii regionu świętokrzyskiego i nie tylko Wirtualna wycieczka do Zachełmia

Wirtualna wycieczka do Zachełmia Projekty unijne

Projekty unijne

Subscribe to RSS Feed

Subscribe to RSS Feed